Personality tests can be accurate and helpful. People taking these tests tend to scare me. For a long time I conflated the test with its takers and thus developed a longstanding, unthought, ideological commitment to freaking out whenever anyone tried to pin my possible personality type. Phrases like “don’t crush me with your overburdened psychological systems” were common. Deliberately confusing the meanings of “sanguine” and “phlegmatic” so I wouldn’t accidentally associate myself with any particular temperament was a habitual exercise. But the problem I have with personality tests — and ultimately, all tests — is really the mode in which we take it, a mode specific to an age shaking terrified with the thought of being a particular person.

Consider a typical personality test. It will ask a series of questions about what we most often do, something like:

1. When you are criticized for doing something wrong, you become:

a) shy

b) angry

c) encouraged

or

2. When you face a problem do you

a) make a plan

b) tackle it head on

Real tests would have more nuance and more options, but let us admit the trend of the questions — we reflect on a hypothetical situation and respond with what we would most likely do.

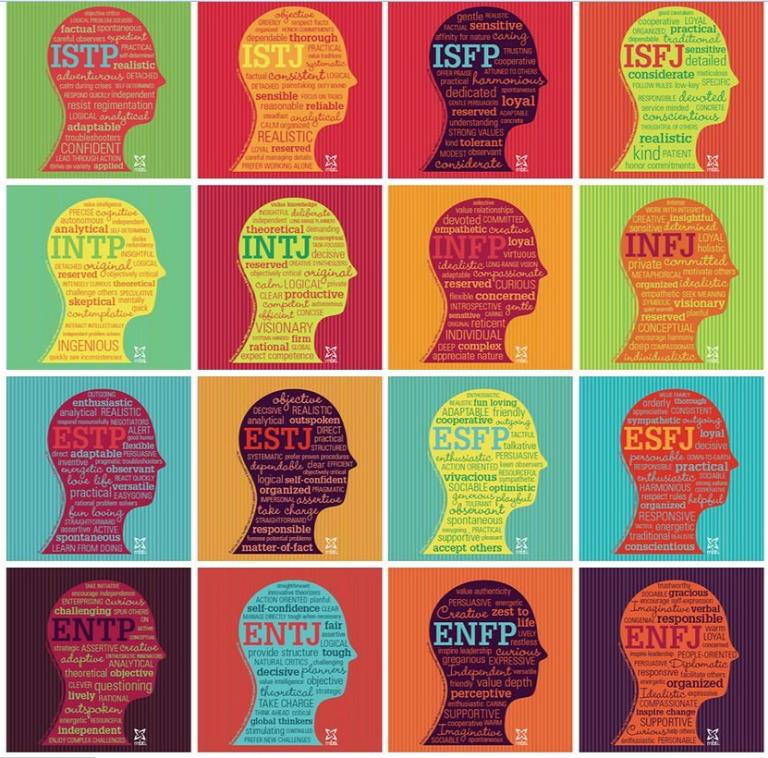

All tests of the Myers-Briggs ilk are tautologies. They are tautological because their results cannot exceed my input. If out of 100 questions, I 100 times affirm that I am likely to grow angry over criticism and confrontation, all my 100-question test-result really says is that “I am likely to grow angry over criticism and confrontation.” Sure, a test may express its tautological conclusions in words that sound like it has digested our answers and excreted some new diamond — as when we tell a test in 100 different ways that we are most likely to look outwardly than inwardly, and it tells us we are an “extrovert” — but closer inspection reveals that this new “identity” is no more than a simplified expression of what we usually do — an “extrovert” is defined as a person more likely to look outwardly than inwardly. The problem with test-takers is that we conflate words which summarize and offer back to us our habits with words that serve as identities given to us by the test. Tests give us helpful tautologies, but we want alchemy, to birth from the meager iron of what we usually do the gold of who we are.

There is an infinite, qualitative difference between what we usually do and who we are. The test-result gives us the former, but can never give us the latter. I believe we suffer from an inordinate desire to ignore this fact. If the test can give us who we are, we can be freed from the responsibility of becoming who we are. Our identity will be told to us. Gone then, the crisis of the American denizen, who is without God, estranged from family, frightened of marriage, hollowed of culture, free from gender, ignorant of history, bored of patriotism, skeptical of ideology, divorced from the land and otherwise speedily running out of any identity-forming values. No longer is he reduced to a stutter over that question of personal identity — who are you? Now, through the test, he may answer in confidence, “told” with authority that he is a heterosexual, a moderate-conservative, an ENFP, a gift-giver and a bi-romantic tactile-learner with ADD and an IQ hardly worth mentioning.

That this illusion amounts to alchemy is no idle analogy. The most satisfying test-taking experience — the one that leaves us with a feeling of really being something — this only satisfies to the extent that it is a magical experience.

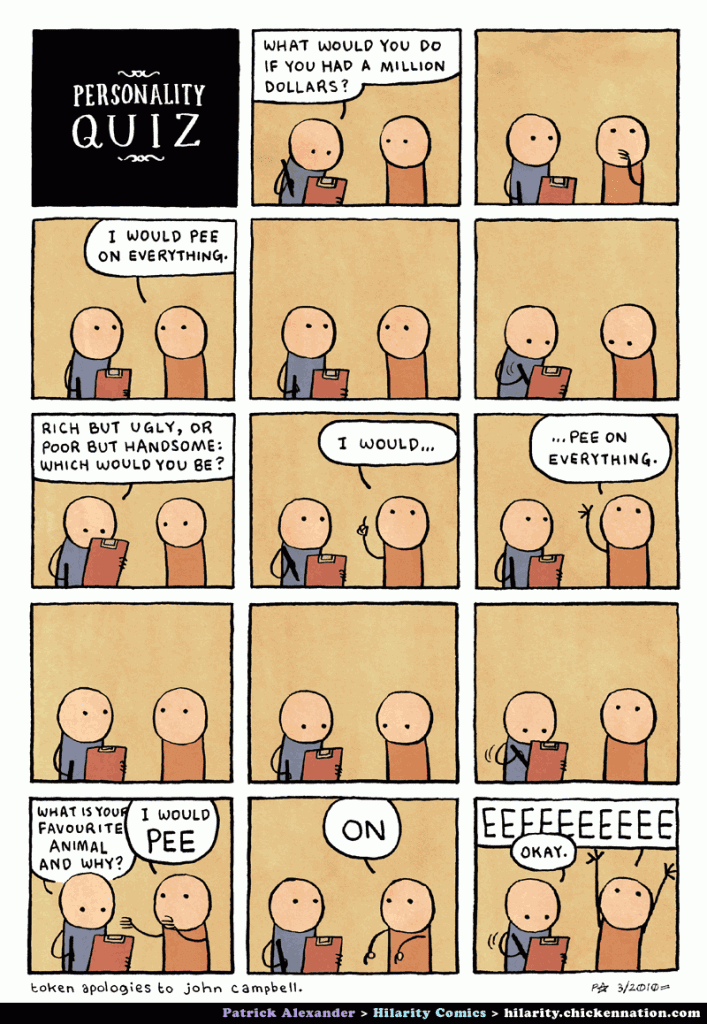

Consider how a satisfying test harbors an air of mystery between our responses and the final test-result. We do not want to “see where this is going” while we take it. There is no fun if we can anticipate the result of our answers. By being able to predict the test we are taking — saying “oh, if I answer it this way, of course it will say I’m an introvert” — we reveal our implicit understanding that the test-result is really only our responses told back to us. We don’t want our responses told back to us. We want an identity. Far better, then, are the questions that obscure the relation between our answers and the final result, asking us for answers we cannot easily connect to some objective personality type. This desire for a hidden mechanism is typical of magical desire — to not know how a result was achieved and to revel in the not-knowing. Can we deny the pleasure we take in this, the powerful feeling that accompanies having our identity so mysteriously given to us, so that we say in astonishment, reading the paragraph that describes our “type” — “How did it know this about me?” It is necessary for us to forget the mechanism of tests if we are to extract identity and not the only thing tests offer — limited reflection.

Another requirement for really enjoyable test-taking is the atmosphere of science.

If we can be assured that a test guaranteeing us new information regarding our sexual identity is a scientific test, we will enjoy the thing all the more, and be far more likely to stand up from it with the feeling of being something — a type. This is not to denigrate the role of the scientific method in the creation of personality tests, but to point out that the test-taker’s faith in the scientific test is nearly indistinguishable from an earlier age’s faith in the shaman, the wizard, or the temple priest. We are not scientific in our faith in the scientific. We are superstitious. We do not assess the test’s claims to “scientific effectiveness” using the principles of repeatability or by an analysis of methodology. We find comfort in the mere claim, in the subtitle “created by a psychologist.” We put our faith in the idea that there is a certain type of person, practicing a certain craft, the wisdom of which is too high for us to attain, reliance on whom will guarantee an accurate result. The massive and trivial trade of Internet personality tests understand this about us, and they advertise accordingly:

Advertisements, because their only goal is to have us click the thing, are useful tools in understanding our motivations. Those hawking personality tests have determined that the best way to get the most click is to use two modes of terminology — magic and science. The tests are “eerie” and “developed by psychologists.”

There is nothing scientific about a faith in experts that enables us to say that our identity is a “scientifically proven” identity, type, or personality — by which we mean nothing more than that it comes from an authority. Indeed, any scientist worthy of his noble profession would shudder at our age’s blatant abuse of his trade, our superstitious adherence to a vague concept of science unworthy of the name. A scientifically arranged test is, in actual fact, a test created with an awareness of its tautological nature, an awareness that all that is being given in the test-result is a probability, a generalization and a repetition of input, “true” only within the framework of the test and in comparison to other test-takers, severely limited by its own parameters and always in need of improvement. But the honorably restrained scope of science is no good for the person seeking a magical jump from what he usually does to who he is. It is far better if “science” is understood as an atmosphere of authority, one that validates his given identity and fortifies it against doubt.

There is nothing scientific about a faith in experts that enables us to say that our identity is a “scientifically proven” identity, type, or personality — by which we mean nothing more than that it comes from an authority. Indeed, any scientist worthy of his noble profession would shudder at our age’s blatant abuse of his trade, our superstitious adherence to a vague concept of science unworthy of the name. A scientifically arranged test is, in actual fact, a test created with an awareness of its tautological nature, an awareness that all that is being given in the test-result is a probability, a generalization and a repetition of input, “true” only within the framework of the test and in comparison to other test-takers, severely limited by its own parameters and always in need of improvement. But the honorably restrained scope of science is no good for the person seeking a magical jump from what he usually does to who he is. It is far better if “science” is understood as an atmosphere of authority, one that validates his given identity and fortifies it against doubt.

Now I know the complaint: There is no one who really believes they are a test-result. And while I concede that no one confronted in this way would ever say “the deepest truth about me is my Myers-Briggs score,” I would argue that there are more ways than these to conflate what we usually do and who we are. Chief among these is the introduction of the test-result into the category of ethics.

And that’s where we’ll pick it up next time.